The past two years in Western Siberia were marked by numerous weather anomalies. At first there was a major dry spell, which began in late autumn of 2011 and spread all over Siberia in 2012: there was so little snow I could hike in the forest in late December wearing my summer shoes, and whatever snow did fall melted away by early March. It didn’t rain at all till late July, a big draught began, with scorched lawns, piles of dead leaves under wilting trees, and dry sand where there had been creeks. Taiga was ablaze – there were so many wildfires in Yugra, Tomsk and Krasnoyarsk districts, that sky all over Siberia was yellow-gray from ash, and you could see spots on the Sun without smoked glass. The Yuganskiy nature reserve, with its old forests, suffered big losses from the wildfires – the reserve workers (both rangers and researchers), armed with little but shovels and spray packs, were dropped off in burning forest from a helicopter in (vain) attempt to stop the fires from spreading. But there’s not much half a dozen men can do with several hundred hectares of burning forest. The fires ceased only in August, when rains came.

The past two years in Western Siberia were marked by numerous weather anomalies. At first there was a major dry spell, which began in late autumn of 2011 and spread all over Siberia in 2012: there was so little snow I could hike in the forest in late December wearing my summer shoes, and whatever snow did fall melted away by early March. It didn’t rain at all till late July, a big draught began, with scorched lawns, piles of dead leaves under wilting trees, and dry sand where there had been creeks. Taiga was ablaze – there were so many wildfires in Yugra, Tomsk and Krasnoyarsk districts, that sky all over Siberia was yellow-gray from ash, and you could see spots on the Sun without smoked glass. The Yuganskiy nature reserve, with its old forests, suffered big losses from the wildfires – the reserve workers (both rangers and researchers), armed with little but shovels and spray packs, were dropped off in burning forest from a helicopter in (vain) attempt to stop the fires from spreading. But there’s not much half a dozen men can do with several hundred hectares of burning forest. The fires ceased only in August, when rains came.

In 2013, the picture was slightly different – the south of Western Siberia (Novosibirsk, Omsk and Altay districts) was literally drenched: there were ceaseless showers with just a few sunny days, and even actual small floods here and there, while in Yugra, in the middle of Western Siberia, the situation of the previous year repeated: blazing sun, crunchy lichens, swarms of sun-loving gaflies over dry peatbogs… and wildfires.

The fires destroyed large areas of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) forest around Ugut, and sad as it was, it meant that we were up to a big mycologicaL event. Fungi play a crucial role in the carbon cycle, which is the never-ending exchange of carbon, the main element of life, between different layers of the living Earth. After a wildfire, this cycle is reset, and in the first few years following the fire a very peculiar group of species take the stage. Some feast on the enormous volumes of fresh coal (having special enzymes for the purpose other species lack), other, having lost their source of food – their mycorrhizal associates, – strive to produce as much offspring as possible from the surviving mycelia before the famine. The process is especially evident in early season, when scores of species appear simultaneously, including many ascomycetes. Burnsite morels are the flagship of the latter.

That’s why we were so curious to see what was going on on burnsites, both in Akademgorodok, where parts of our beautiful Pirogov pine forest had burned out, and around Ugut. Akademgorodok lies at ~55° N, and Ugut at ~60° N, which accounts for an aprroximately two-week phenological lag between them. I was visiting my hometown in June and returned to Ugut later that month. That doubled my chances to see the burnsite frenzy.

First, I went to check fresh burnsites in Pirogov forest in late May. I did find some young Geopyxis carbonaria, Peziza pseudoviolacea, Pholiota highlandensis and Psathyrella pennata on damaged areas (all classic carbotrophs), and quite a few very regular-looking black morels (Morchella cf. elata), but those grew in their regular favorite spots along forest roads, and these spots were barely damaged by fire.

I repeated my attempt two weeks later, and hit the jackpot. The most charred spots were dotted with dozens of young fruitbodies, and the differences between them and regular “elatas” were instantly apparent.

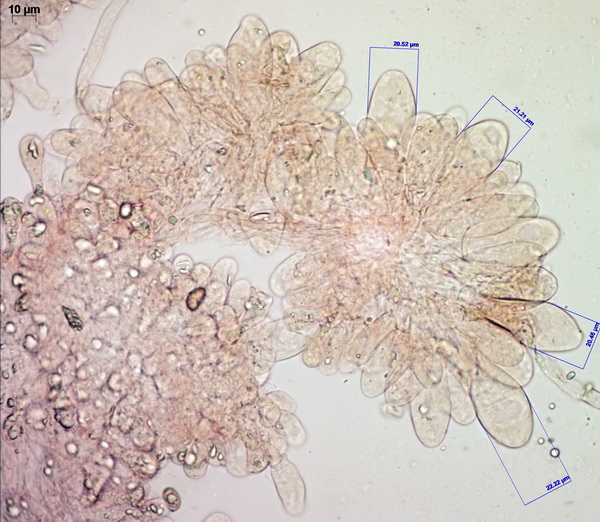

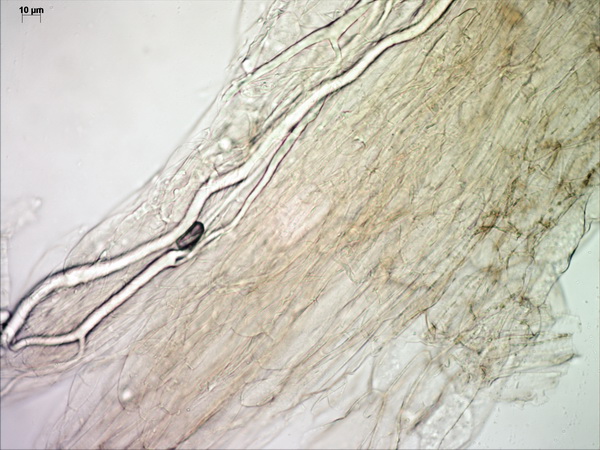

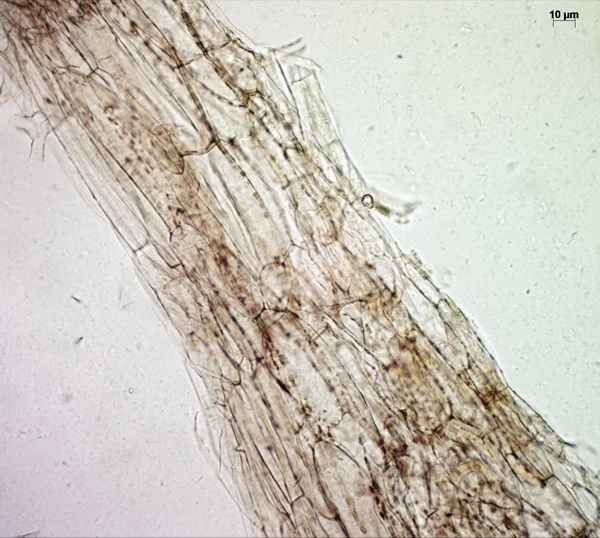

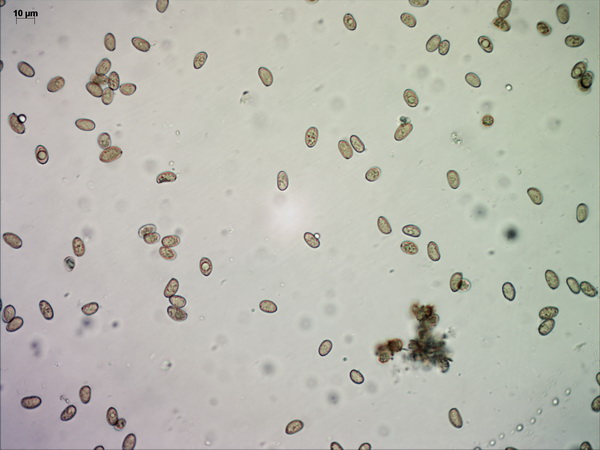

These morels from the second “wave” were more massive, with more numerous ridges and anastomoses, and often with more regular “cell” patterns; stipes of young fruitbodies had a distinct pinkish tinge, and they lacked the warm brown hue (nearly always present in regular “elatas”) until very late stages of development. Their sterile surfaces (“ridges”) had a peculiar silvery-frosty sheen due to the presence of numerous bulb-shaped cells on ridges, which could mean our species is related to the North American taxon Morchella capitata (I haven’t cut our specimens in half yet but the stipes of our collections also seem to be chambered). See the difference for yourself (luckily, I found one slowpoke elata in a shaded pit nearby, it’s on the left… (or at least I hope that it’s M. elata, not yet another cryptic species… 🙂

When I returned to Ugut, Elena and I decided to try our luck on the steep banks of the small river Ugutka which runs along the village. Here’s what we saw:

There were morels everywhere. Their similarity to my earlier find in Akademgrodok was obvious, and while I can’t say for sure it’s the same species, it’s apparently much closer to Akademgorodok burnsite morels than it is to M. elata. The fruiting was so massive that fruitbodies often grew in bundles, up to a dozen in one spot.

they’re not really that fuzzy, it’s aspen seeds stuck to their surface

About an hour into studying the site, Elena found the second item on our wish list – a scrawny yet real “black foot morel” – Morchella cf. tomentosa! Officially this species is known only from North America, but we had found it with Nina Filippova in 2010, making Elena’s the second documented find of the (phenotypical) Blackfoot in Eurasia.

Here it is.

By the time we had… well… documented our finds, we couldn’t feel our arms from hauling basketfuls of specimens. But seriously, this, along with the discovery of Morchella cf. tomentosa near Khanty-Mansiysk in 2010, could be an important find, both mycologically and economically, considering the skyrocketing prices on dry morels worldwide, and the fact that Morels as such are virtually unknown to local collectors, who mostly rely on pine forest porcini (Boletus pinophilus). For these people, losses caused by the disappearance of “hunting grounds” after wildfires in pine forests could be at least partially alleviated by crops of these valuable species that follow.

If you’re interested in burnsite morels, you might find these two articles interesting:

Rebecca J. McLain et al. Commercial Morel Harvesters and Buyers in Western Montana: An Exploratory Study of the 2001 Harvesting Season.

Greene D.F. et al. (2010) Emergence of morel (Morchella) and pixie cup (Geopyxis carbonaria) ascocarps in response to the intensity of forest floor combustion during a wildfire.

a wealth of other morel links can be found on the Morchellaceae page @ mushroomexpert.com (Michael is the expert on morels!).

Few fungi fruited on damaged soil: only

Few fungi fruited on damaged soil: only