There certainly are many brightly-colored fungi out there, but if you want YELLOW, go for Pluteus fenzlii.

Pluteus fenzlii (Schulzer) Corriol & P.-A. Moreau 2007 is a rather unusual representative of the genus Pluteus. It is a strikingly yellow agaric that grows on decaying wood of deciduous trees. It is probably widely distributed, but finds are very rare. In Russia, it’s known from several finds in Central Europe and Siberia.

Speaking of its taxonomy, it used to belong to the poorly known sister genus in the family Pluteaceae, Chamaeota, which includes several rare species of annulate pluteoid fungi (i.e. they look more or less like regular Plutei but have a ring on the stipe). To my knowledge, there have not been any comprehensive studies yet to investigate the relationship between Pluteus and Chamaeota, and it’s possible that there is no distinct borderline between the two genera phylogenetically. A very similar mushroom, Pluteus mamillatus from North America, is also a former Chamaeota (Ch. sphaerospora).

The renaming of Chamaeota fenzlii to Pluteus fenzlii is actually a funny story, because it was done independently by two teams of researchers who published their results within a week, which caused a small fuss reflected in a 2007 article in Czech Mycology.

Elena says Pluteus fenzlii is relatively common in Yugra and collected almost every season. Nadezhda Kudashova, a mycologist from Tomsk, also found it a couple of times and kindly loaned us fragments of her collections as well as a piece of Pluteus fenzlii collected in Krasnoyarsk by one of the most devoted field mycologists in Siberia, Natalya Kutafyeva. I collected it in Akademgorodok in 2012 in a relatively untouched native old birch forest which is part of the Central Siberian Botanical Garden.

Fruitbodies are relatively robust (for a Pluteus); pileus up to 6 cm in diameter, convex to planoconvex, coarsely fibrillose-tomentose, or made up of appressed flocculose squamules, creating a texture very similar to that of the straw paddy mushroom, Volvariella bombycina, and brilliant yellow; lamellae crowded, free, ventricose, whitish, usually with bright yellow edges; stipe 6-8 cm tall, 5-9 mm in diameter, with a small yellow fibrillose ring in the middle or in the lower portion, stipe surface longitudally fibrillose, yellow with paler yellow context showing inbetween fibrils.

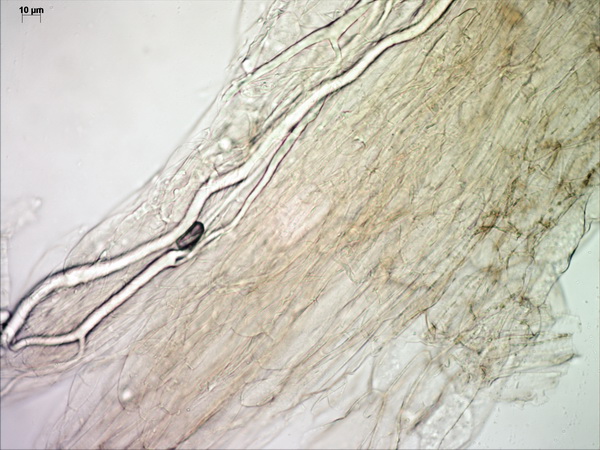

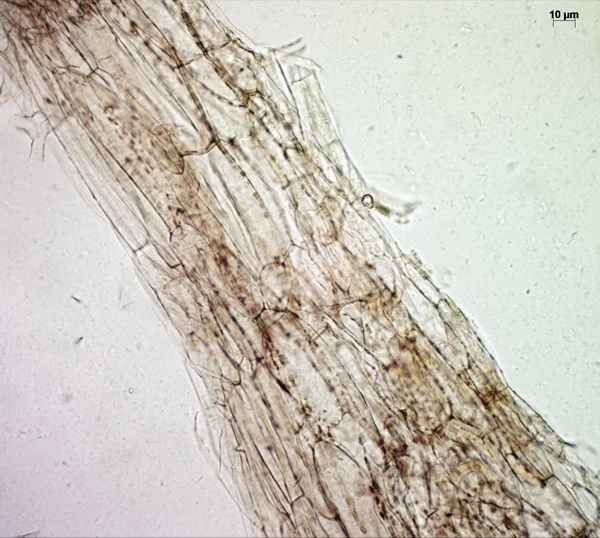

Microscopically, the pileipellis is a trichoderm (literally “hairy skin”) composed of palicaded (i.e. arranged in a tile-like fashion, or appressed) hyphae with slightly inflated terminal elements (tips), with bright yellow intracellular pigment. The stipe surface and annulus are made up of similar elements.

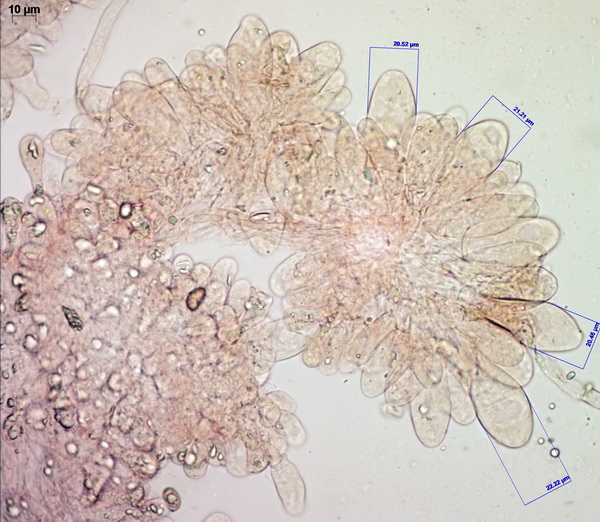

Cheilocystidia very crowded, mostly bluntly fusiform, arising from the lamella trama, bright yellow.

Pleurocystidia colorless, fusiform or fusiform-ventricose, also arising from the trama, often mucronate (with small round tips) or occasionally with small, finger-like or tentacle-like projections from the area around the apex (especially in Tomsk collections). This is an unusual feature which is rarely observed in another yellow pluteus, the Lion Shield (Pluteus leoninus).

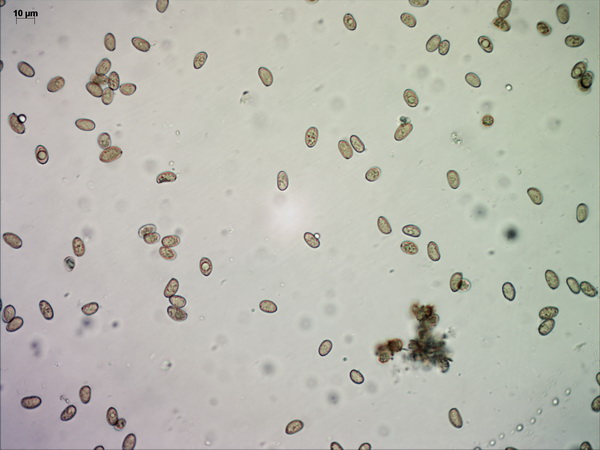

Spores are very rounded for a Pluteus (subglobose to broadly ellipsoid).

Elena found a curious article by Alfredo Vizzini and Enrico Ercole about what appears to be another related species – an annulate form of Pluteus aurantiorugosus. This small species is often confused with Pluteus chrysophaeus, another small yellow species, but specimens described in the paper seem to have the same annulus-like structure as P. fenzlii.